When I began my own research degree back in 2005, I purchased a copy of Patrick Dunleavy’s Authoring a PhD: How to Plan, Draft, Write and Finish a Doctoral Thesis or Dissertation (2003). It was one of the first books that I read during my PhD, and I still read it today. It had nothing to do with the art history of medieval Europe, but it did help me to think about the shape and structure of the PhD thesis. In short, it give me an idea of what the product of a PhD actually is.

Dunleavy’s book is still in print, as are many other books that form the growing sub-genre of academic guidance literature. I believe that one of the reasons for this is that they tackle the whats and the hows of doing doctoral research. Examples might include preparing a literature review or your methodology. In this post I identify two books that I think complement the guidance literature around the thesis, and are a useful addition a researcher’s personal library.

The first is a book by Pam Denicolo, Julie Reeves and Dawn Duke entitled Fulfilling the Potential of Your Doctoral Experience (2018), and the second is the very popular The Bullet Journal Method, by Ryder Carroll (2018). Both are available from the University of East Anglia Library.

At first glance, the contents page of Denicolo, Reeves and Duke appears to be very much about the whats and the hows; in fact every chapter and section begins with those words. But dig a little deeper into the text, and we see that the authors have adopted a much more nuanced approach, reflecting on the motivations, values and assumptions of pursuing postgraduate research work.

It is also a very much about the understanding that pursuing postgraduate research is a personal and a social journey because you are connected to others. It cannot be done in isolation.

A key theme of the text is its engagement, at various points, with tacit knowledge: that is the things that few people tell you, that you are supposed to know as part of that community of practice. It might be the conventions of the elements and structure of the PhD thesis (something that Dunleavy sought to make explicit); what the Quality Assurance Agency (QAA) for higher education thinks a research degree is about; or even what the disciplinary expectations are around a PhD.

Understanding and engaging with this form of knowledge can help students to better consider how to make the doctoral experience work for them, rather than simply being subjected to it. The authors achieve this through a series of activities and reflection points, which reinforce their ethos of empowering the doctoral candidate through options rather than definitive solutions or quick fixes (Denicolo, Reeves and Duke, 3).

Now to our second text. There has been a lot of talk of the BuJo (Bullet Journal) method on social media in recent years. I read the official book on the method, written by Ryder Carroll, and I think that it works well alongside Denicolo, Reeves and Duke.

One of the reasons for this is that, like Denicolo, Reeves and Duke, the whys feature prominently. Although often understood as a combination/intersection of a journal, diary and task list, the Bullet Journal is designed to help understand the purpose of activities in our lives, how they relate to our personal goals, and ultimately support personal and professional fulfilment.

The building blocks of BuJo are the collections. These form the core components of the journal that you set up, and to a large extent are customisable, so can respond to your specific needs as a postgraduate researcher. This is not something that diaries and to-do lists can do because they follow a fixed format (either printed or digital) and are fairly fragmented, so it is common to have different management tools for different purposes. You can see a list of the core collections online.

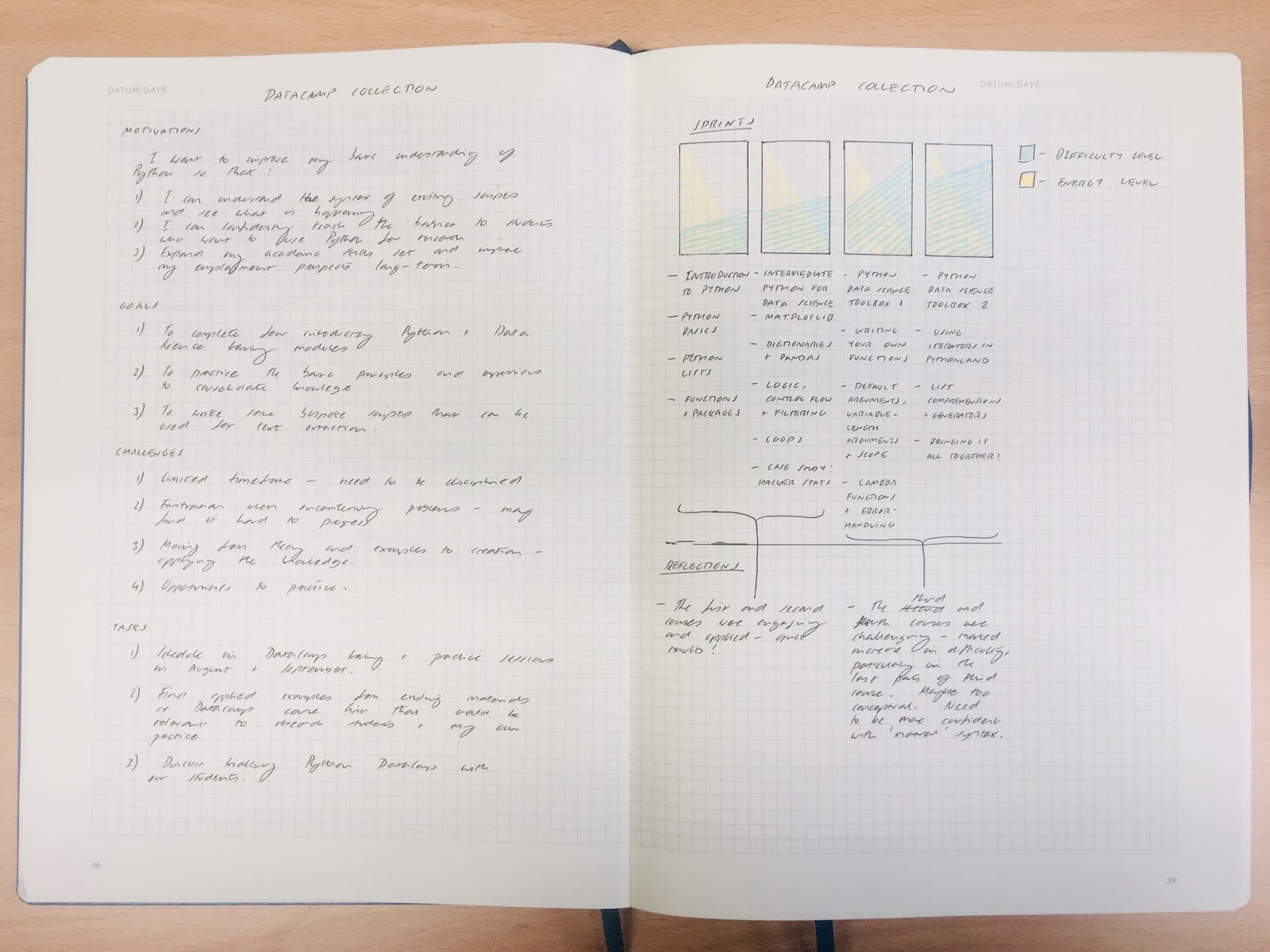

An example of this from my own Bullet Journal is my ‘DataCamp Collection’. It was designed around my aim to learn the basics of the programming language Python. This follows the sprint template advocated by Carroll (157-165), where learning new things, or taking on a major project, may seem like a high stakes, amorphous task. The sprint approach can run over a few weeks or months, and allows you to test out the learning process and decide whether to continue or stop. In short, they provide more realistic and achievable goals.

I focused a lot on my motivations, goals, the challenges and tasks that were involved in the process to be sure of why I was doing this (sometimes easy to lose sight of) and what I was doing at each stage. On the facing page, I used the coloured sprint blocks to indicate the energy level for each stage (which declined over the 3-4 hours per course), but also the perceived difficulty level, which understandably increased as I moved to the more advanced courses. I also logged the main topics that I covered, and then made some reflective notes on my progress at the bottom of the page.

The BuJo approach, then, favours flexibility and efficiency. Flexibility in that your collections adapt to your needs as you move through life, and efficiency in the fact that the tools for productivity and reflection can be found in one place. It is worth noting that the BuJo method has been taken up by our University’s Students’ Union as part of the Courage Wellbeing Project.

Denicolo, Reeves and Duke and Carroll are useful partners for postgraduate researchers because, jointly, they can help individuals to explore not only what is involved in postgraduate research, and what matters, but why it matters in their own life. Both authors, for instance, draw attention to the Five Whys (an approach for finding the causes of problems) created by the Japanese industrialist, Sakichi Toyoda (Denicolo, Reeves and Duke, 125; Carroll, 213). Given that the ethos of both publications is aligned so closely, it is worth examining how a postgraduate researcher might actually use them. As already noted, the BuJo collections principle allows postgraduate researchers to put some of Denicolo, Reeves and Duke’s activities and reflection points into practice. We will look at an example of one of those here: time management.

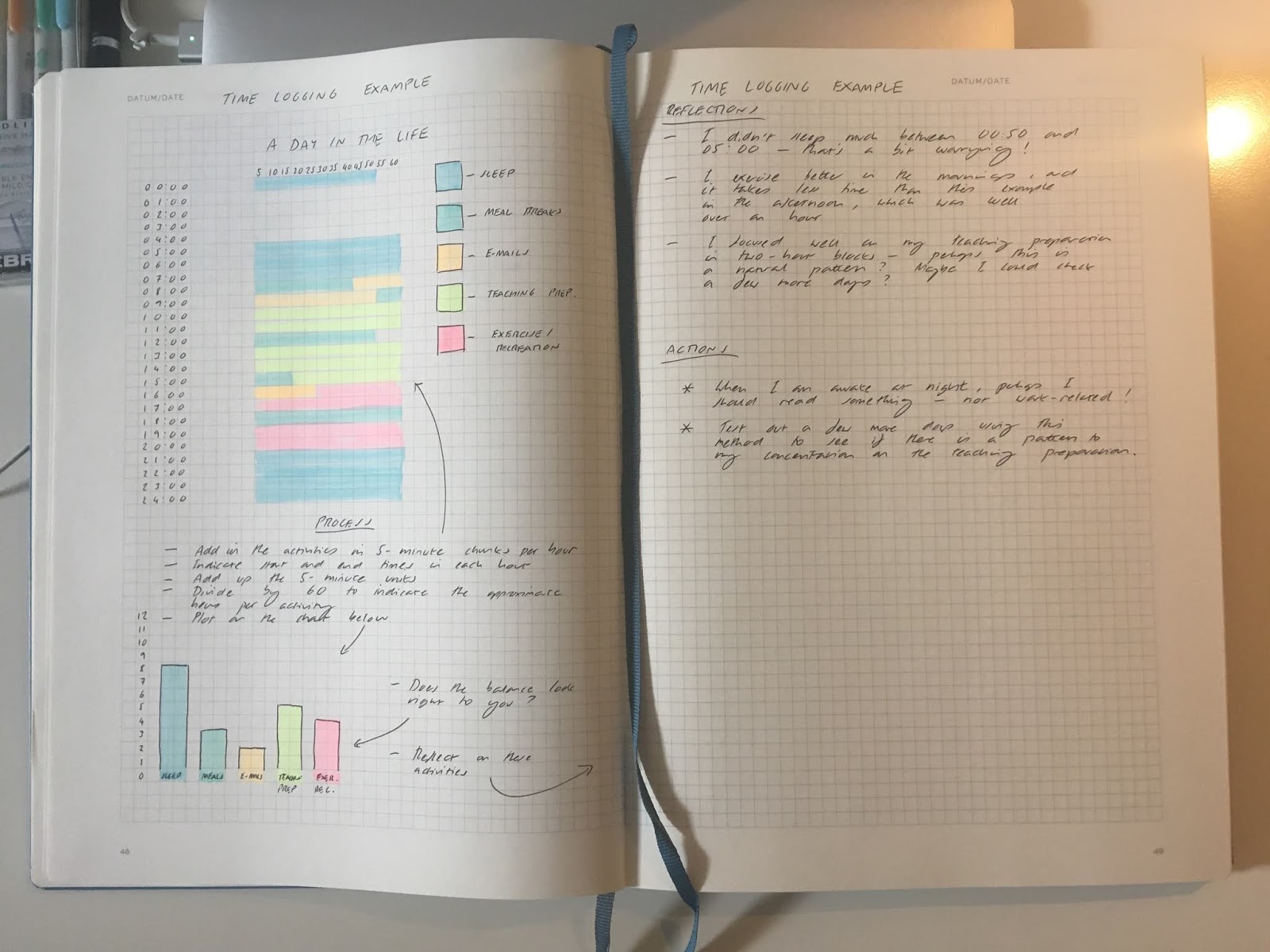

Probably the most terrifying aspect of postgraduate research is how to take time rather than make time. The BuJo approach argues that you cannot do the latter (Carroll, 175-182), unless of course you can manipulate the laws of physics. A research degree is essentially a time-limited project (Denicolo, Reeves and Duke, 18), so planning how your time is used often begins with noticing how you are already using it. Denicolo, Reeves and Duke’s (49) time-logging activity encourages postgraduate researchers to keep a strict record of the time points of an activity, its nature and its duration, over one or several days. It is possible to do this digitally, as the Thesis Whisperer, Dr Inger Mewburn has done. This is handy for quick quantification, but if the aim of this activity is simply diagnostic, then the BuJo approach may be easier (and cheaper) to set up.

The idea behind this is to use the 24-hour clock along the left-hand side and then have an hour represented along the top of the page in 5-minute units. I am only tracking five activities in this example, but if you have more coloured pens, then you could track a lot more. The five in question are: sleep, meal breaks, e-mails, teaching preparation and exercise/recreation (which includes reading for pleasure, walks, going to the cinema, etc.).

At the bottom of the page I have added up the units per activity and divided by 60 to get the approximate number of hours. I then plotted these in the bar chart at the bottom of the page to summarise how the time was being used over the whole day.

If you notice some unusual things (here, for instance, I was awake for four hours in the middle of the night), I can add that to my reflections on the facing page, and consider some appropriate actions.

The BuJo approach is all about learning from your experiences intentionally. Resolving to take action based on these types of observations is likely to be more effective than trying to adopt a system untested, and possibly unfit for your personal attitudes, behaviours and abilities. This is something that I believe Denicolo, Reeves and Duke would agree with.

The combination of these two books provides a way for postgraduate researchers to better navigate the complex interplay of tacit and explicit knowledge that forms the modern research degree. Denicolo, Reeves and Duke’s activities can be done in isolation to tackle specific problems, but when transferred into a Bullet Journal, they could be used as a series of interrelated collections, allowing individuals to adopt their format of activities wholesale or in a different way; perhaps more visually.

As Carroll has noted about his method, a Bullet Journal does not have to be colourful and attractive. It just has to work for its owner. One way that the BuJo method can work very well is through the use of the index. This special collection enables BuJo authors to thread together these activities, and reflections, alongside their future log, monthly log and daily log. These other, essential, collections provide the record of progress and repository of priorities and goals that can help us to be more mindful of why we wanted to pursue a research degree in the first place. It provides a personalised response and companion to Denicolo, Reeves and Duke’s demystification of the doctorate and call for empowerment through greater knowledge and understanding.