Background

This blog post is based on a workshop delivered at the Vitae Researcher Development International Conference 2018. It begins with a review of current initiatives at the University of East Anglia that provide continuing professional development for postgraduate research supervisors. Drawing on a blended model of supervisor CPD employed with the Faculty of Arts and Humanities (part online, part workshop-based), it examines the advantages and limitations of the problem-based model informed by policy and institutional procedures. In doing so, we will consider the opportunities and challenges of a person-oriented approach that focuses on enhancing supervisory pedagogy and supporting researcher/supervisor wellbeing to improve the experience for both parties.

The workshop emerged from the changes in supervisor continuing professional development that have been implemented at the University of East Anglia over the last nine years. At the outset, supervisors were effectively ‘briefed’ on changes in institutional policies. As time went on, we looked more closely at the procedures that both supervisors and students were involved in (e.g. monthly reporting mechanisms, annual progress reviews, probationary requirements, interruptions to study).

Knowledge of policies and procedures is vital for all staff members connected with postgraduate research as it potentially avoids miscommunication, incorrect advice on what needs to be done, by whom and when. It also allows for clarity at the start of a student’s candidacy so an individual know’s what the institution expects, and what they can expect from their institution.

From 2013, we have used scenarios to examine some of the problems that can emerge in the course of a doctorate (Eley and Jennings 2005). These case studies, although fictionalised, were often seem by supervisors as quite plausible (sometimes so similar to situations that have heard of or experienced, that they thought they were based on real events at the university). Although each scenario illuminated aspects of the personal life and relationships of the student and supervisor, they are based on and tend to perpetuate the same idea: that the PhD student is problematic.

Sometimes, when creating online resources for supervisors, or drafting new scenarios, I am conscious that I am dealing more with problems than people. This is the crux of this workshop. I want to believe that we are, in higher education, interacting with people. People with hopes, dreams, histories, successes, failures, fears and aspirations.

How, then, do we get closer to the person in supervisor CPD? I believe that it is possible by focusing on a third ‘p’, and that is pedagogy. Doctoral pedagogy has received considerable attention in recent years, with increasing numbers of papers contributing to methods, approaches and models of doctoral learning. This workshop will introduce just a few of these that I think can contribute to a person-centred approach in supervisor CPD; that is, building a culture for learning that is based on a different concept of the doctoral candidate.

Managerialism

Kathryn Owler’s (2010) article on the nature of the PhD as problematic emerges in the wake of increasing work by researchers on the university today: its operation and its qualities in a globalised world. Several related terms have emerged connected with the UK university: ‘managerial’, ‘corporate’, and ‘bureaucratic’.

As Deem, Hillyard and Reed (2007) have noted, this has come about because of wider ideological and organisational trends of ‘New Management’ and ‘New Public Management’ seen elsewhere in the private and public sectors, a view echoed by Ronald Barnett (2011, 46) who identifies increasing bureaucracy within the UK university, such that ‘the list of procedures expands and each set of procedures becomes more complicated’. Owler, similarly, (2010) highlights the negative effects of ‘managerialism’ within universities, where non-completion is often cast as a form of ‘mis-management’.

Emotional intelligence has a significant role to play in postgraduate research supervisor continuing professional development. Although also seen as another manifestation of ‘managerialism’ - in this case ‘self-management’ (Owler 2010, 292) - wherein the individual needs to take initiative to manage themselves emotionally (and by extension manage others emotionally), it is undeniable that a positive emotional state in both students and supervisors would support doctoral learning.

Recent work on mental health and wellbeing among the postgraduate research population, locally, through our University’s ‘Honesty Project’ (2015), in national studies by Vitae on wellbeing and mental health, as well as professional development provision (2018, 2017) shows that there are considerable pressures associated with doctoral research, and that failure to properly understand students’ emotional states perpetuates poor relationships, departmental cultures and increases the risk of withdrawal and damaging for the student’s self-image. Calls to address this, through Catalyst funding (2018) have led to strategic priorities, such as our University’s ‘Courage Project’.

Although Owler is right to call for subjectivity and a recognition of the unique qualities of the research experience for each student, it does not mean rejecting or denouncing the policies and procedures that have emerged in higher education. What is needed, however, is a person-centred approach to these experiences of policy and procedure as it is enacted.

A Person-Centred Approach

There is, I believe, a way to provide another lens on supervision, and one that aims for a greater clarity. This emerges from the work of psychologist, Carl Rogers (1980, 114-117) who proposed the ‘person-centred approach’. Rogers’ ethos was based on three core principles:

- Genuineness, realness, or congruence - the person is present as themselves in the relationship

- Unconditional positive regard - positive acceptance of what the other is feeling or saying (non-judgemental)

- Empathic understanding - sensing accurately the feelings and personal meanings of the other

This is very much a philosophy that focuses on actualisation: the realisation of our abilities, not the disintegration of them (ibid. 117-128). Applying this to the problem/person lens means that through the ‘problem lens’, we take a view that the student will tend toward disorder and disintegration. Note some of the language used in documents, such as ‘isolation’, a ‘lack of communication’ or lack of effective ‘integration’, or ‘non-completion’. These are very good observations, but they seem to diagnose the symptoms rather than the condition. They are built on the view that the student is inherently entropic. Focusing exclusively on policies and procedures often leads to treating the symptoms.

Rogers, I think, would disagree with the approach. He would start from the position that the student is syntropic; tending towards fulfilment and self-actualisation. This individual may become more complex, but also be able to function emotionally and cognitively with this complexity. One of the syntropic tendencies is that of developing greater awareness. This is awareness of our actions, of feelings, or behaviour, our relations to the world. This mental framework (primarily conscious, but acknowledging the unconscious) is a means of understanding ourselves.

The role of the supervisor is also to adopt a greater awareness, of themselves as people and as educators, but also a deeper understanding of the students that they supervise.

Active Listening

How does a supervisor achieve this? Rogers (1980, 116) outlines the importance of active listening, which allows the therapist or educator to better ‘hear’ the client or student - to better empathise, and finally to understand. In a sense, this is to think with the other.

Søren Bengtsen’s (2016) recent work on active listening is somewhat different. This is not something that can be divorced from the disciplinary content - the knowledge - that student and supervisor are engaged with:

‘The fact that doctoral supervisors listen, actively, for something in particular - as opposed to whatever the student wishes to say - is what most significantly sets active listening in doctoral supervision apart from active listening in clinical and therapeutic contexts. Doctoral supervisors and students listen actively for highly specific and deeply disciplinary content. Consequently, active listening in doctoral supervision is actually not about the person being supervised, as it would be in clinical and therapeutic contexts; it is less about the person and more about the content.’ (Bengtsen 2016, 115).

Bengtsen’s conclusion is based on his own empirical work. It is clear that supervisors are employed in this form of listening and discussion as thinking, and thinking with their student. We can take Bengtsen’s findings on board, but what does this mean for a person-centred approach, if conversations are not about the person? Perhaps the clearest answer comes from Rogers again, who places emphasis on hearing and on being heard, and understood. There is, for Rogers, a clear personal sense of wellbeing from being understood:

‘If we think, however, that empathy is effective only in the one-to-one relationship called psychotherapy, we are greatly mistaken. Even in the classroom it makes an important difference. When teachers show evidence that they understand the meaning of classroom experiences for students, learning improves.’ (Ibid. 155)

In many ways Bengtsen’s work actually complements Rogers’. Although Bengtsen’s research allows us to focus on thought, on a more subject knowledge or project-based approach, I would argue that it is still strongly related to the person; taking that individual seriously as a thinking, changing entity.

Active ‘thought-listening’ does not mean ignoring the person; rather it is actually compatible with the idea that the person is being heard and valued as a contributor to scholarly discourse, that they are finding a ‘voice’. They are not speaking into the void. As Rogers notes, ‘…empathy dissolves alienation.’ (Rogers 1980, 151). Empathy allows the ‘voicing’ noted by Bengtsen (2016, 117-121) to emerge.

Feelings and Learning

Emotion and learning, in Rogers’ person-centred approach, are closely connected. He notes that ‘[t]here should be a place for learning by the whole person, with feelings and ideas merged’ (Rogers, 1980, 264).

This very much reflects Owler’s (2011) view, where doctoral researchers have, themselves, claimed that the doctoral experience is a personal one, not simply about fulfilling certain criteria (and it is through our policies and procedures that we establish and address these). Recent work by Frances Kelly (2017), has highlighted the concepts of the ‘ideal’ and ‘fully-developed’ researcher as very much part of a global, neoliberal agenda often seen as responsible for the managerialism afflicting universities.

Kelly’s ‘ideal’ researcher is one that combines the personal and professional, self-manages and is mobile; one who also makes a significant economic and social contribution (ibid. 49-51), but essentially exists as part of a hegemonic discourse of individualism.

The ‘other’ researcher: the one who is does not quite conform to this productive, almost subservient model, is one who may be subject to the irrational in their motivation to research in the first place. This alleged irrationality leads to a tension in the idea of the knowledge worker (ibid. 55-58).

The same author also examines the idea of the modern, ‘fragmented’ academic - one that is many things to many agendas, working across and between disciplines and professions. For some this can be deeply disconcerting, but for others a way of defining a new ‘self’ (ibid. 58-62).

What the doctoral experience may be able to provide are the conditions for understanding and integrating these academic experiences, which is founded on one of the main three principles of the person-centred approach: congruence. There is a drawing together of experiencing and feeling, as Rogers notes:

‘So if I were to attempt a crude definition of what it means to learn as a whole person, I would say that it involves learning of a unified sort, at the cognitive, feeling, and gut levels, with a clear awareness of the different aspects of this unified learning.’ (Rogers 1980, 266).

Pedagogical Behaviours and Techniques

So, what are the pedagogical techniques and tools in doctoral-level learning? What is it that supervisors could/should be doing with their students to support a person-centred approach?

The starting point for pedagogy, as I have noted, is syntropic. We need to appreciate what it is that the individual values in undertaking their research degree. We can achieve this through active listening and creating an environment where the student is free to ‘be’. No requirement to justify, impress, or hide. This might be said to form the core of the pedagogy.

Active Listening

Active listening techniques will include attending to the words, the surface meaning, but potentially also other meanings. The active listener will also attend to the physical behaviour of the student, such as body language.

Active listening will involve responding by accurately repeating (not necessarily verbatim) what the student is saying, and possibly trying to say. It may involve clarification, perhaps some negotiation, of what they are thinking and feeling about an issue, but it should come from the student, not the supervisor.

See: Li and Seale 2007; Brearley and Hamm 2013; Godskesen and Wichmann-Hansen 2013; Bengtsen 2016

Prizing

‘Prizing’ is a term borrowed from Rogers (1980, 271-272). It is bound up with ‘acceptance’ and ‘trust’, but the reason I believe this to be important is that the academic culture of criticism can neglect a positive approach. Critique can become synonymous with negativity, and does not facilitate learning and growth.

Understanding a student’s thinking (through discussion and their writing) should reveal when moments of difficulty arise, perhaps academic challenges are faced. These should be marked, identified and prized as part of the learning process. Silence or admonition may not reinforce how these experiences are formative and contribute to an identity.

See: Rogers 1980; Robertson 2017

Reflective Writing

Attending to the affective and the cognitive can be supported through writing. As writing is an embedded practice of doctoral research, and most forms of doctorate will require it, writing can become part of supervision encounters and ongoing research activity. Both supervisor and student can use reflective writing in their interactions.

See: Brew and Peseta 2004; Manathunga, Peseta and McCormack 2010; de Caux et al. 2017

Cognitive Apprenticeship

Scaffolding learning processes enhances metacognition. Supervisors can support students by slowing down the thinking process and making behaviours and tasks within academia much more explicit. This might involve modelling those behaviours, but they are fundamentally situated (not abstract). Metacognition makes quantitative and qualitative management of knowledge more visible.

See: Collins 2006; Austin 2009; Posselt 2018

Academic Literacies

An academic literacies approach looks at the ways that knowledge is enacted in the academy, and the cultural practices operate in communities of practice. This may involve examining conventions, what counts as knowledge, and the identity and position of the researcher. It may also address uncomfortable ‘truths’, namely the power relations involved in research activity, or the reason for different approaches in different fields.

See: Magyar and Robinson-Pant 2011; Bastalich, Behrend and Bloomfield 2014

Conclusion

I hope that this blog post has provided a window onto different conceptions of supervisor CPD in two ways. The first is by framing the way institutions and individuals approach CPD with the tendency to see the doctorate through a problem lens. In doing so, it is possible to lose touch with the unique qualities of the doctoral experience, as highlighted by Owler. Fundamentally, though, it risks problematising the person.

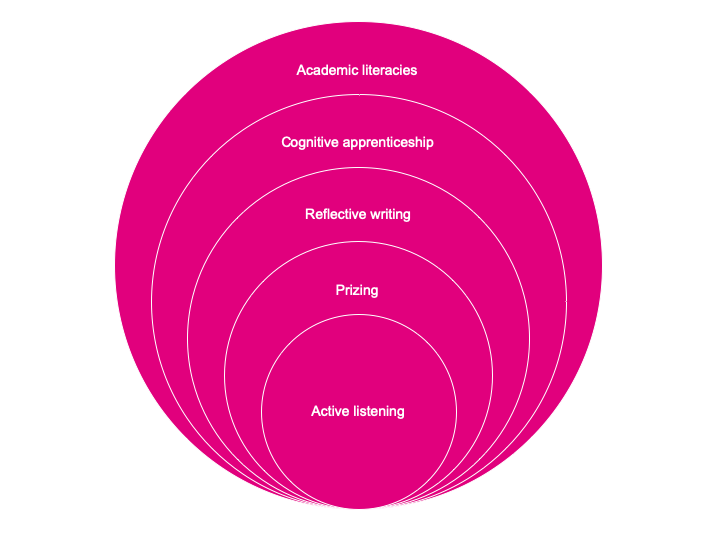

The second is through a person lens. Although by no means a new educational philosophy, it can be implemented through supervisor pedagogy; that is, the person-to-person interactions. Active listening, reflective writing, cognitive apprenticeship, academic literacies and prizing are all pedagogical behaviours and techniques that anchor the doctoral experience with the individual.

Through these it is possible to integrate some of those key policy and procedure concerns around responsibility, ethical practice, and professionalism. They do not have to be incompatible with creativity and risk-taking in research. Uncertainty is in fact a key part of QAA descriptor for research degrees. How supervisors and students cope with it is as much one of attitude.

The attitude proposed here is one of syntropy: that there is a move towards complexity within the individual, fulfilment and self-actualisation. We must begin with the premise that students are people with a formative tendency, not problems waiting to happen.

References

Austin, A. E. (2009). “Cognitive Apprenticeship Theory and Its Implications for Doctoral Education: A Case Example from a Doctoral Program in Higher and Adult Education.” International Journal for Academic Development 14: 173-183.

Bastalich, W., M. Behrend and R. Bloomfield (2014). “Is non-subject based research training a ‘waste of time’, good only for the development of professional skills? An academic literacies perspective.” Teaching in Higher Education 19(4): 373-384.

Bengtsen, S. E. (2016). Doctoral Supervision: Organization and Dialogue. Aarhus, Aarhus Universitetsforlag.

Brearley, L. and T. Hamm (2013) “Spaces Between Indigenous and Non-Indigenous Knowledge Systems: Deep Listening to Research in a Creative Form”, in Peters, M. A., and A. Engels-Schwarzpaul, A. Of Other Thoughts: Non-traditional Ways to the Doctorate: a Guidebook for Candidates and Supervisors. Rotterdam: Sense Publishers.

Brew, A., T. Peseta (2004). “Changing postgraduate supervision practice: a programme to encourage learning though reflection and feedback.” Innovations In Education & Teaching International 41(1): 5-22.

Bruce, C. and I. Stoodley (2013). “Experiencing higher degree research supervision as teaching.” Studies in Higher Education 38(2): 226-241.

Cahusac de Caux, B. K. C. D., C. K. C. Lam, R. Lau, C. H. Hoang, and L. Pretorius. 2017. “Reflection for learning in doctoral training: Writing groups, academic writing proficiency and reflective practice.” Reflective Practice 18(4): 463-473.

Collins, A. (2006). “Cognitive Apprenticeship.” In The Cambridge Handbook of The Learning Sciences, 47-60. Cambridge, Cambridge University Press.

Deem, R., S. Hillyard, and M. Reed (2007). Knowledge, higher education, and the new managerialism. the changing management of UK universities. Oxford, Oxford University Press.

Eley, A. R. and R. Jennings (2005). Effective Postgraduate Supervision: Improving the Student-Supervisor Relationship. Maidenhead, Open University Press.

Godskesen, M. and G. Wichmann-Hansen (2013). “Aktiv lytning i ph.d.-vejledning - et værktøj til udvikling af dialogiske kompetencer.” Dansk Universitetspædagogisk Tidsskrift 8(15): 145-157.

Hill, G. and S. Vaughan (2018). “Conversations about research supervision – Enabling and accrediting a community of practice model for research degree supervisor development.” Innovations in Education and Teaching International 55(2): 153-163.

Kelly, F. (2017). The Idea of the PhD: The Doctorate in the Twenty-First Century Imagination. London, Routledge.

Kumar, V. and E. Stracke (2017). “Reframing doctoral examination as teaching.” Innovations in Education and Teaching International: 1-9.

Li, S. and C. Seale (2007). “Managing criticism in Ph.D. Supervision: a qualitative case study.” Studies in Higher Education 32(4): 511-526.

Magyar, A. and A. Robinson-Pant (2011). “Special Issue on University Internationalisation–Towards Transformative Change in Higher Education. Internationalising Doctoral Research: Developing Theoretical Perspectives on Practice.” Teachers and Teaching: Theory and Practice 17(6): 663-676.

Manathunga, C., T. Peseta, C. McCormack (2010). “Supervisor development through creative approaches to writing.” International Journal For Academic Development 15(1): 33-46.

Metcalfe, J., S. Wilson and K. Levecque (2018). Exploring wellbeing and mental health and associated support services for postgraduate researchers. Ghent University and the Institute for Employment Studies. Cambridge, Vitae (CRAC).

Owler, K. (2010). “A ‘Problem’ to Be Managed? Completing a PhD in the Arts and Humanities.” Arts and Humanities In Higher Education 9(3): 289-304.

Posselt, J. (2018). “Normalizing Struggle: Dimensions of Faculty Support for Doctoral Students and Implications for Persistence and Well-Being.” The Journal of Higher Education, 1-26.

Rogers, C. (1980). A Way of Being. Boston, Houghton Mifflin Company.

Robertson, M. J. (2017). “Trust: The Power That Binds in Team Supervision of Doctoral Students.” Higher Education Research and Development 36(7): 1463-1475.

Taylor, S. (2016). UK Professional Standards Framework (UKPSF) Dimensions of the Framework for Doctoral Supervisors, Higher Education Academy.

Taylor, S. (2018). A Handbook for Doctoral Supervisors. London, Routledge.

Taylor, S. and A. McCulloch (2017). “Mapping the landscape of awards for research supervision: A comparison of Australia and the UK.” Innovations in Education and Teaching International: 1-14.

Thouaille, M-A (2017). One size does not fit all: arts and humanities doctoral and early career researchers’ professional development survey. Cambridge, Vitae (CRAC).

University of East Anglia Students’ Union (2015). The Honesty Project: Postgraduate Research Mental Heath at UEA. Norwich, University of East Anglia.